You consider yourself a fight fan?

Sit back and enjoy reading this talented sports writer Scott Yaniga’s take on boxing with his column Ring Wise featured here every month on the River View Observer website.

Welcome to the debut of Ring Wise on the River View Observer website. Join us as we explore The Sweet Science of Boxing, both past and present. Readers are always welcome to send a comment, question or story suggestion along to us, via the email address at the end of this issue’s column – Scott Yaniga

R.I.P. Jose “Chequi†Torres

When we think of the world of boxing and its inhabitants, probably the last thing we consider is the intellect of the persons wearing the gloves and trunks. Yet, by virtue of writing two of the best books on two of boxing’s most compelling figures; writing a regular city side column for The New York POST; being a political activist and campaigner for Bobby Kennedy, as well as being a regular at legendary literary boite, Elaine’s, former world light heavyweight champion Jose “Chequi†Torres transcended the sport and became a man of letters.

Torres, also the New York State Athletic Commissioner for several years in the 1980’s, passed away in his home in Ponce, Puerto Rico on January 19th, leaving behind a legacy of not only fistic, but intellectual talent seldom seen in this, or any other sport. He was the author of ‘Sting Like A Butterfly’, one of the best biographies about Muhammad Ali, as well as ‘Fire and Fear’, a fine study of a young, troubled Mike Tyson.

Always a popular figure on the New York boxing scene after retiring from the ring wars, one was guaranteed to witness a loud, boisterous ovation any time Torres was introduced in the ring at Madison Square Garden, it’s little brother in the basement–The Felt Forum, or at Sunnyside Gardens in Queens. He was part of the great New York City triumvirate of champions that included world heavyweight champion Floyd Patterson and world lightweight champion Carlos Ortiz, all of whom received heroes’ welcomes when attending the fights.

It was a love affair that never really ended for Jose Torres.

Around ten years ago, the champ came to the place of business where I toiled in mid-Manhattan, expecting to have lunch with my boss, fight manager and boxing film magnate, Bill Cayton. Cayton had gotten delayed at another meeting uptown and had to beg off his luncheon date, leaving Torres sitting in our waiting area. I had a passing acquaintance with him, having made several video reels of his fights for him to show to friends and family, but was unprepared when he entered my work area and said, “My friend, have you had lunch?†Needless to say, I jumped at the opportunity.

Walking the several blocks distance to the unassuming spot Torres picked in the Garment District for our meal, our journey was stopped at least half a dozen times by an assortment of New York’s working class. A doorman here, a bicycle messenger there, a man pushing a rack of dresses, a UPS man waving and shouting from his truck, and one older gent who stopped in front of ‘Chequi’ and then squared off with him in pantomine, smiling all the while. Mostly all were of Latino extraction, and all looked thrilled to see and speak to him.

Torres’ gracious demeanor towards his street-side fans never wavered, his broad, flat-nosed face creased deeply with a smile as he chatted easily in Spanish and signed a couple of autographs. The adulation continued at the restaurant as one of the busboys–a guy at least as old as the Champ–and one of the cooks, a guy younger than the sports coat Torres was wearing–came over to our side of the counter to talk to him in rapid-fire Spanish.

It was remarkable to me that he would still be enjoying the kind of attention after all the years of being out of the spotlight, but then I realized that Torres, long an advocate for the working class Hispanics in New York, had never really been out of the consciousness of “his†people. He wrote, broadcast and made personal appearances on behalf of many social causes within the Latino community, and was as revered in 1999 as he was in 1969.

Lunch didn’t allow for many discoveries about Torres the man or Torres the boxing champion, with the conversation being dominated by the subject of Mike Tyson, who back then was serving a second stint in prison, this one for beating up two motorists after a traffic altercation. Torres was one of the inner circle around a young, pre-championship Tyson, when his awesome talents were still being honed in the incubator known as Catskill, New York, by his old trainer and Svengali, Cus D’Amato.. He had great insight into what made Tyson work, as exhibited by some of the recollections contained within ‘Fire and Fear’.

Torres was not angry at Tyson for flushing away one of the most promising legacies in boxing history; he was more disappointed and sad at what could have been. He was saddened that the life plan as laid out by the late D’Amato was now trashed, along with Tyson’s career.

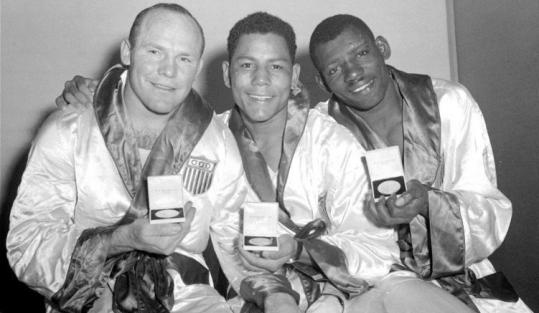

Jose Torres was born in Playa Ponce, Puerto Rico in 1936, represented the United States in the 1956 Olympics in Sydney, Australia, where he settled for a silver medal, losing to the legendary Lazlo Papp in the finals of the light middleweight division. After the Olympics, he was trained by the eccentric genius Cus D’Amato and worked out of the Grammercy Gym that D’Amato owned on 14th Street in New York City. Torres continued to excel in the amateur ranks, winning both a National AAU title, as well as the 1958 New York City Golden Gloves Open title in the 160-lb. division. Torres, fighting at the middleweight limit, turned pro in May of that year, knocking out Gene Hamilton in the first round at the old Eastern Parkway Arena in Brooklyn.

After reeling off twenty-seven straight wins with 20 knockouts, Torres hit a brief roadblock in his career when he was dispatched in five rounds against the lethal-punching Florentino Fernandez in Puerto Rico on May 25, 1963. It would be the only stoppage suffered in his career, and Torres–who was smartly outboxing Fernandez until getting caught–learned from his loss, vowing never to get too cocky in the ring after that. He rebounded well, taking a hard-earned decision from the underrated Don (brother of middleweight great Gene) Fullmer in October of the same year. Torres, now fighting in the light heavyweight division, ran up seven more wins after that, including a first round blowout of former middleweight champion Carl ‘Bobo’ Olson, who by that time was a shot fighter.

The impressive win streak resulted in a title shot against smooth-boxing world light heavyweight champion Willie Pastrano in Madison Square Garden in March, 1965. The younger, better-conditioned Torres outwitted, outhit and finally stopped Pastrano via technical knockout after nine rounds of one-sided action. In an odd move, considering he had just won the world light heavyweight crown, Cus D’Amato had his man fight a non-title tenner against tough journeyman heavyweight Tom McNeeley in Puerto Rico in July, 1965. Outweighed by 25 pounds on fight night, Torres labored in the hot, humid confines of Hiram Bithorn Stadium to maneuver away and box McNeeley from a distance. McNeeley had no fear of Torres knocking him out, so he took the fight to Jose, mauling him on the inside and using a variety of elbows, shoulders, kidney punches and other assorted, mischievous fistic moves to make Torres’ night a long one. While he won the decision, many felt that it was this fight that had ruined Torres in some ways, taking away his formidable sense of self-confidence and pride. In winning a meaningless, non-title bout against a fringe heavyweight contender, Torres and his psyche had been mugged by the rough house tactics of the bigger, stronger McNeeley.

It was thought that D’Amato had designs on Torres eventually fighting Muhammad Ali for the heavyweight title, an obsession he suffered with since another of his fighters, Floyd Patterson, had lost the title to Sonny Liston in 1963. But the foray against McNeeley–no Ali he–cured him of any such fantasies. Torres then defended his title successfully three times before losing to fellow Hall of Famer Dick Tiger in December, 1966 at Madison Square Garden. The aggressive Tiger tamed his prey, as a reluctant Torres allowed the talented Nigerian to dictate the pace and intensity of the fight, losing the decision by three wide votes. Their rematch in May, 1967, again at the Garden, was a complete turnaround as a well-conditioned and hungry Torres, his pride stung by losing championship gold the last time out, met Tiger head on and gave a great account of himself.

The resulting split decision loss to champion Tiger resulted in a near-riot, with folding chairs, bottles and trash of all kinds being tossed into the ring. Fistfights broke out around the arena and the NYPD had to call in reserves to bring the arena under control. Torres took almost a year off, coming back in April, 1968 to stop the unheralded Australian Bob Dunlop in six rounds in Sydney.

On July 14, 1969, Torres was scheduled to fight Buffalo’s Fightin’ Jimmy Ralston at Madison Square Garden. Ralston injured his elbow right before the fight and had to check into a hospital, leaving Torres with no opponent for the night. Charlie ‘Devil’ Green, a sparring partner for Torres, was convinced to substitute for Ralston, assuaged somewhat by the promise of some quick cash and Torres’ assurance that he would take it easy on him.

Near the end of the first round, following some routine jabs, body shots and blocked punches, Torres went heavy into Green’s body, causing the unpredictable (Green would eventually be convicted of murdering three people in a drug-fueled rampage) club fighter to lose his temper and flail out at Torres with a quick combination, putting the ex-champ on the canvas. He was revived enough to come out for the second round and quickly found himself confronted with a Green who was seeking the biggest win of his mediocre career. Torres summoned up the champion’s reserve he still had inside him, landing a beautiful and devastating five-punch combination that put Green down and out on his face.

Rest in peace, champ.